In the event that I am aboard a helicopter that crashes into the sea, I can survive. I'm certified.

Last week I took a trip over to Robert, Louisiana, where Shell Oil has a large training facility for most everything related to offshore oil production. It was the command center when BP's Macondo well blew out, sunk a rig and led to one of the worst oil spills in history. It's a place dedicated to education and safety - you are even required to back in to all parking spots to minimize the risk of auto collisions (a requirement, a later learned, that is actually common at work sites throughout the oil industry).

It is also home to one of the Gulf Coast's most renowned centers for HUET training, or Helicopter Underwater Egress Training. It is a class required of most everyone who might ever go offshore in a helicopter. Of course, that population is made up almost entirely of people who work in the oil industry - not just the roughnecks and roustabouts that work on the drilling rigs and production platforms but also the crews of supply ships and support vessels for those same facilities. And of course the parasite reporters who cover such things.

Shell had invited me and a couple other reporters to come check out the Noble Bully I drillship, which is drilling for the oil company about 70 miles off the Louisiana coast at the Ursa/Mars prospect in the Gulf of Mexico. It would take about a day to get there by boat, but only an hour or so by helicopter. Since we'd be flying over water - and since helicopters have a nasty habit of, well, crashing - we needed to be trained in escape.

The class kicked off around 7 am and began with a few terrifying videos of sinking sea ships and fleeing sailors. That was enough to get us to pay attention. The instructor said, quite soberly, that the most important thing you need to have in order to survive is something worth surviving for. For him, it was his wife, kids and grandkids. Maybe it's a girlfriend, he said. Maybe it's a cherry car. Whatever it is, you need to keep that thing in mind at all times if disaster does strike.

We proceeded to learn some nifty survival stats and strategies. The instructor extolled the virtues of life jackets, which may seem kinda obvious. But it turns out that, especially in cold waters (less than 59 degrees F), a life jacket can triple your chances of survival. In waters that cold, you won't survive more than one or two hours because the coldness will wear your body down. But with a jacket, even in frigid seas, you can survive up to six hours. Don't take 'em for granted.

Other tips: If there is a group of you lost at sea, lock arms in a circle and kick in three- to five-second blasts to create a pulse effect. It creates a target of whitecaps visible from the air. Kick in short bursts so it looks like a signal. Also, beware of static electricity caused by chopper blades when they lower a cable to pull you from the water - it'll travel right down the cord and the hook. Let the hook hit the water first so the static electricity dissipates.

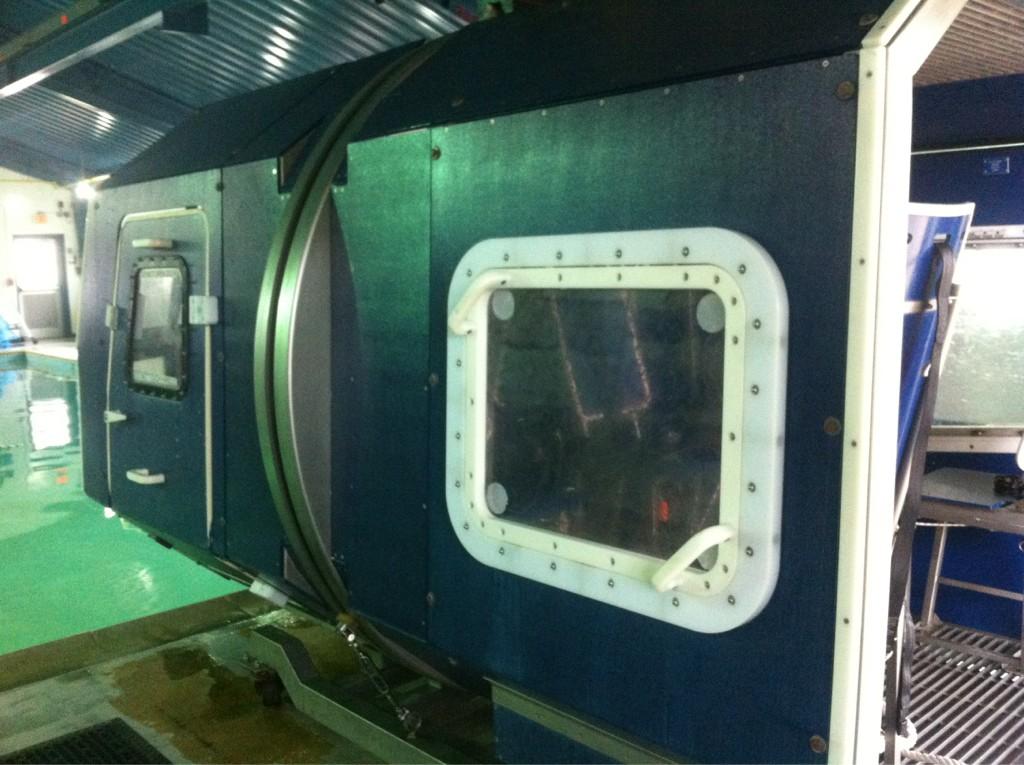

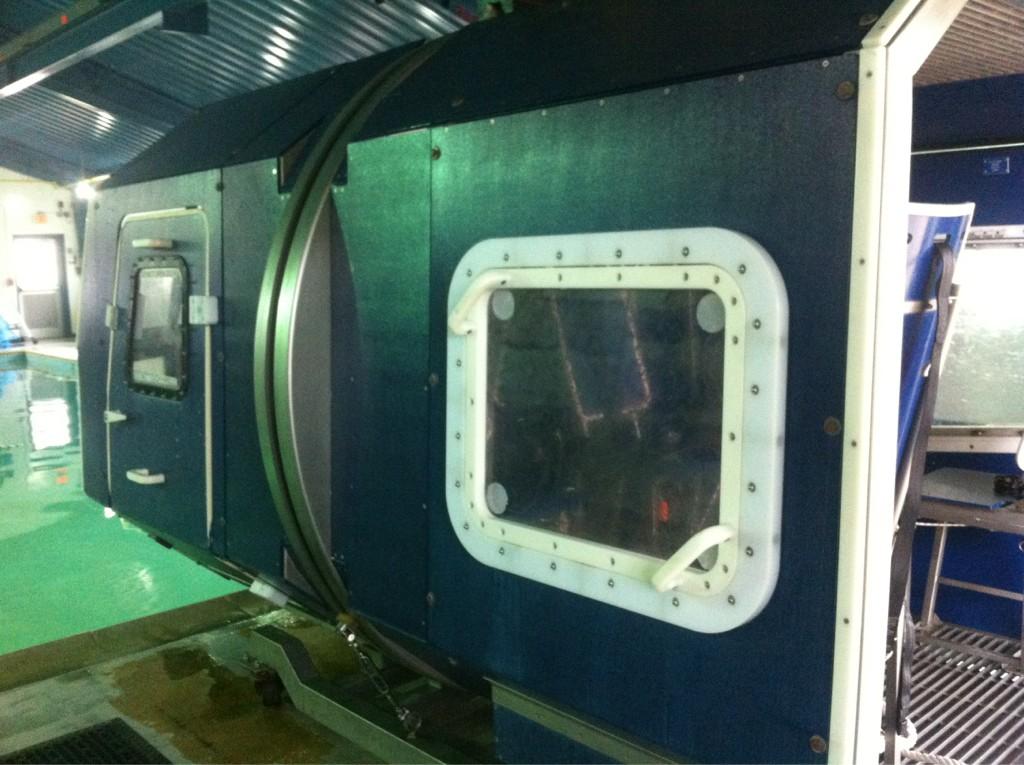

That's all helpful info, of course, but that is not the aspect of HUET that gets the people buzzing. In the afternoon, we moved to the pool. We performed progressively harder underwater tasks like swimming through doors, inflating our coveralls as a flotation device, and so on. Then came the main event - the dunking.

The pool is equipped with the shell and spartan innards of a faux-helicopter cabin attached to a mechanism that lowers and spins the whole contraption upside down. Four of us at a time sat in seats inside, strapped in by a seatbelt, and were instructed on how to jettison the windows and the doors. After punching them out, you must find and grip a reference point so you don't get more disoriented and can find your way out when the frigid seawater rushes in (although we were in a heated pool during training).

"You are trying to experience disorientation and panic," the instructor told us.

And so there we were, strapped in to our simulated disaster cab. "Brace for impact!" someone shouts.

"Brace! Brace! Brace!"

We clutch our seat belts for dear life as the vessels crashes into the surface of the water. The cabin quickly fills. It's up to our ankles and then our knees, and then the whole thing starts to flip. Stomach, shoulders, neck - quick! take a breath because it may be your last! - and we're submerged, and still flipping.

Air bubbles everywhere as the water shoots up my nose and into my ears. The disorientation is kicking in heavily now. We must wait before the violence subsides and the vessel comes to rest before we can punch out the windows. We must remain strapped in even through this so the rush of water does not throw toss us around the cabin.

I'm upside down and searching for the handle that's supposed to jettison the door. I can't find it. Panic is beginning. Somehow my hand glances it and I'm able to push it open as my stolen breath moments earlier at the surface is reaching the end of its life span. I weakly get the door off and clutch for the seat belt latch. It comes off stubbornly and, using the reference point of the top of the open doorway, I push myself out and barely make it to the surface - arms flailing, as instructed, to clear the path of any potential debris from the crash - and gasp for breath. Safe. Alive.

Click here to see my video of what happens (on the surface).

This is not embellished. I actually needed a little assistance from the scuba team that served as a safety net for this particular run-through. I had to do it again in order to pass the class, and pulled it off slightly smoother, or at least with less panic and no help from the scuba guy. The upside down thing is tough because, to jettison the door, you have to reach down a bit to find the latch. When upside down, you actually have to reach

up a bit. It's tricky when disoriented to begin with.

Nevertheless, I am now certified. Two days later, I and some of my classmates flew out. We made it to the rig and back with no problems, thankfully. But I knew that, if we ditched, I would have shit my pants.